Heritage Happenings

Welcome to Heritage Happenings, a daily series of little snippets to stimulate curiosity for your local place during this time of social distancing and cocooning.

On your 2km radius walk each day, keep an eye out for things you never noticed before. It might be a flower in a hedge, a tree, an unusual postal box, an iron gate, building, monument, butterfly or even a placename.

If you want to know more about it, send us a direct message or post it to this page and we will try to help you.

Likewise, if you are cocooning at home, we hope this page will provide you with a little diversion. Please feel free to send us your observations about the topics as we go along. We’d love to hear from you.

From Shirley, Your County Heritage Officer.

Day 1 – Primrose

At the moment, the hedges and ditches of Monaghan are erupting with pale yellow flowers, custardy smooth on the main petals with a golden colour to the centre. These are primroses, or in Irish Sabhaircín, and the latin primula means first flower. They are typically a deciduous woodland and hedgerow plant, as they like the earthen banks and the dappled shade.

Folk maintained that they bloomed in Tír na nόg, and that if you visited this place of eternal youth, especially out of season, that you would bring back a bunch as proof of your visit.

It was traditionally considered to a protector of the home and the farm. Its medicinal properties medicinal included as a cure for jaundice, the flowers boiled in milk and drank each morning. It was also rubbed on cow’s udders to encourage them to produce milk. On May eve, it was used to protect against evil influences and fairies and was laid on doorsteps or windowsills.

Day 2- Blackthorn

It’s coming into flower now, tiny white flowers in profusion on the blackish branches amongst the very sharp long thorns. Blackthorn is a very useful shrub or tree for pollinators as it comes into bloom so early in the season, and later in the year it will produce sloe-berries. Some people painstakingly gather these, prick them, cover them in sugar and gin and make sloe gin. Blackthorn can send out suckers and can spread quite easily, colonising areas that are not cultivated and as a result are good at establishing areas of scrub and young woodland.

In Knockatallon, I was asked “are you cutting your stick” – in other words – was I leaving? Indeed, I was, but I did not cut myself a blackthorn walking stick, sure that is a skill in itself. I understand that those who know about these things keep an eye out for good straight sticks as they grow over a few years, so that they can select the best. These sticks were considered useful to keep fairies away during the night.

In Irish, blackthorn is called Draigheann. In Latin, it is Prunus Spinosa, very much sounding like a spell that would be cast in Harry Potter.

If you were turned into a blackthorn, you would feel very prickly indeed.

Day 3-Flat-bar gates

Made in forges by local blacksmiths, these pleasing farm or pedestrian gates are made by stretching and hammering red-hot rolled iron on the anvil. An anvil is a large heavy piece of cast or forged iron with a flat top.

At one time, every local area had a forge, with a hot fire and bellows for pumping in air to keep the embers red. These forges provided a good livelihood for a skilled blacksmith and often an apprentice, who made their own tools for working, and tools for others in the community – farming tools, gates, cranes for kitchen hearths, pots for cooking, shoes for horses. The forges were the very centre of the community, real centres of alchemy. Indeed, blacksmiths were often said to have cures, but more of that in another Heritage Happenings.

A flat-bar gate is made by striking flattened iron, forged together with rivets and often decorated at by pinching the iron into little shapes at the tip of each piece. The latch, a very functional part of the gate, was often decorated with quite a flourish, each blacksmith having his own preferred design. Some gates even have extra little levers so you could open the gate from the top without dismounting from your horse. On the slam bar, which is the piece where it closes you can often find the name of the blacksmith stamped in the iron while it was still hot. A small advertisement at the time and valuable piece of history now. The gates probably sound out a “right clatter” when closing still.

If you are out and about, you might find some nice examples of these gates, why not have a fresh look at them. These gates are irreplaceable and can still be repaired by a few skilled blacksmiths.

Day 4-Wood anemone

These are woodland flowers and are a rather beautiful clue that an ancient woodland was once in the location where they are now found. Ancient woodland is woodland that existed from before about the year 1700. It flowers early in the year before the woodland canopy closes, so you will hopefully see it. Anemones form lovely drifts on the woodland floor or under hedges.

Wood anemones spread vegetatively, they creep along – only 6ft every 100 years. So gorgeous, their carpets of fresh green divided leaves have white nodding heads of flowers in the morning, cupped close. Then as the six petals open to track the sun during the day, they are like bright snow stars amongst the green.

The word anemone comes from the Greek word for the god of the wind, the Irish for wood anemone is Lus na Gaoithe (herb of the wind), and scientific name is Anemone nemorosa.

The photograph of wood anemone shown here is from the townland of Kilcran, a placename that has been interpreted in two ways, both mentioning trees. Coill Chrann – the wood of the trees or Cill Crann which means Church of the trees. Either way, it’s placename tells us that there has been a woodland here for many centuries, which is a very satisfying thought indeed.

Day 5-Blue tit

You will probably be familiar with these little busy birds, strikingly turquoise blue and yellow, always flitting around. Blue tits are common in most habitats, gardens, parks, hedges and woodland.

In Irish it is Meantán gorm (gorm means blue). it has a dark stripe running from its beak around its eyes like a striking eye mask. Its’ crown is bright blue and wings too, underneath is yellow. While it prefers to eat small insects, it will also eat seeds. Blue tits nest in small cavities in trees or walls, and often will use a nest box or some cosy place like a post-box.

The blue tits you see now are most likely building nests, filling them with moss and animal hair and starting to lay tiny eggs. They can lay a clutch of up to 14 eggs, over a period of two weeks but the mother bird won’t start to incubate them until the last one is laid. They want to make sure their chicks hatch when there is peak food availability.

The hard work for the endearing blue tits is only beginning. When the eggs hatch, they will be on the go constantly working to feed the hungry brood of scaldies. Scaldie derives from the Irish scalltan and was always the word used in Monaghan for young birds or nestlings.

A little folklore around blue tits are that if the first bird a girl sees on Valentine Day is a blue tit, then she will live in poverty. Charming.

Blue tit photograph credit Richard Duff.

Day 6-Hilly placenames

Monaghan abounds in drumlins, hills of mixed clay and stones that were shaped as the ice melted during the last Ice Age. These distinctive features, usually have a gentle slope to one side and a steeper slope to the opposite side, representing the direction of the ice melt or retreat of the glaciers. Other hills are what I would call pointy, or round all around, perhaps with a very stubborn rock core. All great for rolling down or sliding down on a plastic bag during the winter snow!

This topography is reflected in placenames in the county. Do you live on a Drum…, a Cor…?

Drum refers to the droim, meaning ridge or a back like an animal lying down. Some examples are Drumirril or Droim Oirill in Farney. Drumgeeny or Droim Géine in Truagh, which means ridge of the moss. Boggy and therefore mossy habitats are common in Truagh. The amazing Sphagnum or peat moss can hold up to ten times its dry weight in water. More on this in another Heritage Happenings.

Corr is typically a round hill, a pointed hill, a conspicuous or odd hill. Corracrin or Corr an Chrainn is Round hill of the trees.

Knock or Cnoc means hill as well, and is more commonly heard in the north of the county. Knockballyroney in is Cnoc Bhalile Ui Ruanaidh, Hill of the homestead or town of the Ruanaidh (surname).

Tully or Tulach is a hillock. Tullynarney or Tulaigh na nAirne is tulach na n-áirneadh or hillock of the sloes (berry of the blackthorn).

You can find out more about your townland name at www.logainm.ie

Day 7-Ringforts

In Monaghan, many of the gaelic Irish continued to live in ringforts right up until a few hundred years ago. On hill tops, you can often see a copse of trees, or prominent earthen banks still.

Ringforts were essentially farmsteads and some are fossilised into placenames such as Lios, Rath, Dún. Liscat is Lios cat or Fort of the cats. Rakeeragh is Rath caorach or fort of the sheep. Dunmaurice is Dún Muirisc or Muirisc’s fort.

Ringforts were usually circular and had a diameter of 20 to 50 metres, with a ditch and earthen bank marking the perimeter. Inside, there was usually a circular house made from post and wattle with a thatched roof. Farm animals were kept inside the ditches for safety at night-time. These sites are now on the archaeological register for Ireland and are protected.

The website www.archaeology.ie has a useful, easy to use, interactive map where you can see aerial photographs and old maps depicting ringforts and other archaeology. Here is a link to one to in Monaghan at Lisseraw or Lios an Rátha – essentially ‘fort of the fort’, which is a great description as it does appear to be triple banked fort. So good they named it twice!

You can see the ditches and banks quite clearly, and the way the field boundaries radiate out from the top of the hill.

The registration number is MO013-020.

Day 8-Whins

Whins or the whin bush is the common name for gorse in Monaghan, that very spikey, dark green leaved shrub with the golden, fragrant, buttery soft flowers. Bright vanilla gorse. On Easter Sunday there is a tradition which combines eggs and whins in Ulster, a custom full of Easter symbolism.

The first delicate task is to pinch the blossoms from between the thorns, trying to avoid laceration at all costs. The yellow petals are then boiled with the eggs. All participants climb to the top of a steep hill to then race down behind their chosen golden egg, which can be eaten, gratefully afterwards.

In Irish, gorse is aiteann, which is a combination of aith (sharp) and tenn (lacerating). In early Irish law, gorse was one of the ‘bushes of the wood’ and was useful for making hedges and shelters for livestock.

In latin, it is Ulex europeaus. To me, Ulex always sounds thorny.

Day 9-Small Tortoiseshell butterflies

These are on the wing now, meaning that they are no longer caterpillars, and have metamorphosed successfully into flying jewels. Orangey in colour, with black and yellow bands to the front of their wings, and almost a lacey effect around the edges in black and blue, they have it all going on. A bit of Bett Lynch dress sense!

As caterpillars, they nibble nettles and live in little groups until ready to make their cocoon, when they separate and go it alone to be in social isolation. In late Spring, they emerge as butterflies to enjoy the air, the spaciousness and the freedom which is suddenly theirs.

They love buddleia flowers, and you are bound to see them in your garden or on your walk on a sunny day.

In Irish they are Ruán beag.

Day 10: Reeds

Elegant rose gold reeds frame our lakes beautifully at this time of year, setting off the reflected blue sky or the muted foggy grey water to perfection. Reeds like to have their feet wet and their purple-ish feathery heads blowing about in the air. They are commonly found fringing lakes or in marshes and fens across Monaghan county and across Ireland.

Common reeds are Ireland’s tallest native grass and can grow to over 2metres, with very tough stems to keep them upright. Remains of reeds have been found in the peat at the bottom of raised bogs, proving that these places were once lakes.

In a time when roofs were mainly vegetative, reeds were used for thatching houses, but not as much as one would think, perhaps they did not last so long as other materials – “Sometimes empty reeds found growing beside lakes” are used for thatching, recorded in Corlattallan in 1946.

Between 1835 – 1840, a survey of houses showed that most were still thatched, except for Glaslough, County Monaghan where only 35% of the houses were still thatched, showing the influence of a landlord in improving conditions there.

Reeds are excellent at absorbing nutrients and play a role in water purification, so good in fact that they are used as the main plant at constructed wetland sites, including the water treatment wetlands at Castle Leslie, Glaslough.

It’s latin name is Phragmites australis, pronounced Frag as in Fraggle Rock – if you recall that children’s television series. In Irish, reeds are giolcach.

The photographs are from Killyboley Lake, Glaslough or Coillidh Bhuaile, the wood of summer pasture

Day 11- Spy windows

Traditional houses in Monaghan and elsewhere often had spy windows in their jamb walls. Nothing to do with actual spies, or James Bond though.

The jamb wall was opposite the front door of the house, adjoining the central hearth, keeping the heat in while allowing the light from an open front door to permeate through. The spy window was at the right height to see who was approaching the house for a ceilí (social visit), without leaving a warm spot beside the fire. This house type has been characterised as a “hearth-lobby” style house.

It is thought that this innovation was introduced by British settlers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The jamb wall is also known as the speer-wall, spike-wall, spy-wall or hollan.

The position of the jamb wall allowed the creation of a little lobby inside the front door, especially where there was no porch. It also meant that large animals like cows could no longer enter the house, and so a separate byre was required. These hearth-lobby houses were a step up from the byre-dwelling combined houses, where the hearth was at one end, and the few milking cows were tethered at the opposite end wall, with a simple drain dividing the areas.

Windows were small, about face-sized, mostly square or near enough, but a few homeowners took an opportunity to be a bit creative and sported triangular spy windows in the jamb wall.

You might notice traditional or vernacular houses that are derelict on your walks, or you may still live in one and be preserving this lovely heritage. We often forget how far we have come, and how much we’ve forgotten.

Day 12-Lords-and-Ladies

These are one of the oddest flowers you will see in the dappled shade of a hedgerow, or woodland edge, but at this time of year it is the large arrow shaped leaves that are most apparent. As well as its unique form, lords-and-ladies or cuckoo pint has a very special and close relationship with small flies or midges. A fine romance.

Keep a close eye on these arrow shaped leaves, as very soon they will throw up a sheath or spathe, which hides within a dull purple spadix. The sheath opens during the day and the spadix heats up to give off what must be an unpleasant smell as it attracts the small midges. Don’t sniff it, you might inhale the little beasts.

The captured fly falls down into the base of the spadix where it pollinates the flower, and then the stiff hairs inside the sheath die back to allow the fly to escape and perhaps carry this plants pollen to another lords-and-ladies. The flies never learn about the danger of entrapment, albeit temporary!

Later in August, the spadix becomes a fruiting body, prominent in the hedgerow base, shining with bright red poisonous berries.

The plant seems to prefer lime-rich soils and its distribution may reflect the presence of former woodland.

Their scientific name is Arum macalatum and in Irish is Cluas Chaoin, smooth or crying ear.

Day 13-Burial ground symbolism

Historic burial grounds in the county are a repository of symbolism and folk art, inscribed on the faces of old headstones and memorials. Part of a south Ulster tradition, which seems to have travelled from Scotland with the stone masons and settlers in the a 17th and 18th century, these symbols of mortality include crossed-bones, skulls, hour-glass, coffin and a bell.

The meanings of all this heady symbolism hardly requires any explanation, for that was their purpose – to remind the visitor that one is mortal, that time on the earth is finite, and that the bell will toll for us all. This morbidity was a commonly expressed at the time, the headstones themselves a reflection of religious oratory, not yet having moved to the more cheerful cherubs and praying figures that adorn the slightly later headstones.

Many of these mortality symbols in county Monaghan are to be found on the back of small discoid stones, looking like stunted wheeled crosses, very economical in terms of the quantity of stone needed and reminiscent of the Irish high crosses. A real combination of cultures.

One renowned stone carver, called William McKay (a Scottish name) was buried in Donagh graveyard, close to Glaslough. He was of nearby Glennan quarry and is thought to be one of the stone carvers responsible for the unusual headstones found in the south Ulster area. This old monastic site was essentially fossilised through the new use of headstones for family plots from the 17th century onwards, with three 1666 memorials still in place today amongst the other stones, cross, ruins, lichen and mosses.

Today, 18th April is the International Day for Monuments and Sites, with a theme of Shared Cultures, Shared Heritage and Shared Responsibility. Many historic graveyards in Monaghan and elsewhere are important heritage sites, with significant and protected ruins, memorials and histories of religion, cultural divisions and integration expressed in their remains. These sites are special places for those who visit and safeguard them. The Heritage Council has an informative guide available on their website on the Care and Conservation of Historic Graveyards which will be of interest to those with a role in caring for these sacred sites.

The photos are from Killeevan Old Abbey graveyard, County Monaghan. Killeevan is Cill Laebhan, the church of Laebhan.

Day 14- Bluebells – odd candles not fork handles

Bluebells are one of the most evocative spring flowers that we have, easily recognisable and numerous where they have the right habitat to carpet the ground. The resulting mesmerising blue haze is joy for the next few weeks.

Bluebells or Coinnle Corra in Irish, translating as odd candles, can push their young shoots through deep leaf litter on the woodland floor and compete their lifecycle over a matter of a few weeks before the woodland canopy closes. Their underground bulbs can produce leaves and flowers at the same time. The bulbs produce a sort of gummy sap, which in the past was used for bookbinding and setting tail feathers on arrows. In County Monaghan, it has been recorded as a medicinal application for whitlows, those little abscesses in the soft tissue near fingernails.

Bluebells are rich in pollen and nectar and very much loved by bumblebees, who are its chief pollinator, able to squeeze into its dangling bells. It is one of the plants that are indicative of old hedge or woodland, and often is found with Lords-and Ladies, lesser celandine and wild garlic, all of which also have useful underground storage.

Extensive areas of bluebells bloom on Black island at Lough Muckno and at Rossmore Forest Park, but it is also prominent in hedgerows in smaller dainty clusters.

Cloigín gorm is the name children learn at school for our little blue hyacinth, and Bú seems to be a much older Irish term.

Photos are Bluebells emerging with greater stitchwort at Seaveagh in a hedgerow, and bluebells at Kilcran, County Monaghan.

Day 15-Mossy carpets

Patrick Kavanagh’s Green Fool mused that “a man who cannot find happiness and content in a turf-bog is a bad case.” He was no fool, as to stand on the living surface of a turf-bog, is to be upon a rich carpet of sphagnum mosses, a hummocky quaky mosaic of colour; mosses which can engineer their own landscape.

Sphagnum mosses can hold twenty times their own weight in water. Water is trapped between the moss plants in a hummock but also within the special barrel shaped cells of the plant itself. To grab a handful and squeeze is like turning on the tap, so much water will pour out.

The storage of water continues even as the dead moss accumulates as peat. It does not decompose as other plants in the wet acidic environment it creates for itself – this is how bogs store carbon. They are carbon sinks, the plants are standing on their ancestral peaty remains, and have the best capacity of any ecosystem to store carbon. Bogs are vital to retain and restore in our fight against climate change and for this we need sphagnum moss to be able to actively grow.

The mossy hummocks can be 1m high on the bog and can be chocolate brown or orange. Others form loose mats in pink, red, copper and yellow. Others grow as single plants surrounded by water in bog pools. These ones are bright lucid green. As sphagnum moss plants are just one stem each, there can be 50,000 plants in just square metre.

Sphagnum is known for its medicinal and antiseptic properties, and it is recorded that Brian Ború used it at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014. It produces an antibiotic called sphagnol.

During the First World War, the collection of moss was managed from all over Ireland, by women relatives of Irish regiments in the British Army. The moss was separated, graded, washed and packaged in regional depots and then sent to the Royal College of Science on Merrion Street, Dublin. It was then sown into fabric for various applications.

In Monaghan, we have collected information on 711 wetlands, many of which have sphagnum mosses actively growing. The short video shows two young naturalists finding out how much water sphagnum moss can store, filmed on the blanket bog of Sliabh Beagh. More about wetlands in another Heritage Happenings!

Day 16

Curlew, cry some more in the air

The curlew is an unusual tweedy brown bird with a long, curved beak like a cobbler’s needle, useful for probing soft ground for its dinner or small invertebrates. To match this quirky innovation, it also has a whistle like call often referred to as a “cry”. WB Yeats heard the curlews lament “O Curlew, cry no more in the air” and Robbie Burns heard its whistle and felt an “elevation of the soul”.

Robbie Burns soul would therefore feel loss at the dramatic collapse of the population by 86% over thirty years in Ireland. As did many more people, so after public pressure and advocacy for this special bird, the Curlew Conservation Programme was established.

Today, 21 April is World Curlew Day. Only 6-7 known breeding pairs of Curlew remain in all of County Monaghan. They like wide open bogs and meadows in Monaghan, and they lay their eggs on the ground so are very vulnerable to predators.

If you are lucky enough to hear or see one between April and July you can help by reporting it to the local Curlew Action Team who will work with farmers and land owners to help conserve the breeding efforts of the bird.

In Irish, curlew is Crotach, which also means crooked which indeed its beak is.

For those who have forgotten the Curlew call, the sound of Curlew calling can be found at the link below.

Thank you to Donal Beagan for the photograph of the chicks and some information for this piece.

Day 17-Earth homes

One beauty of mud walled houses is that the main building material is usually close to hand, no travel miles. Another is that the earth is warm and insulating, although it needs good coat of lime render to keep it watertight. They have a gently softness about them as homes, almost a blurring of the edges.

The area around the Dromore River system in Monaghan – now named Rockcorry, but the old Irish name is Buíochar – from ‘yellow land’ on account of the yellow clay – less rock, more clay, has more mud houses than anywhere else in the county.

Houses like this must be built slowly, a couple of feet at a time, then drying and then another layer. Often the windows and doors were cut out afterwards with a spade, and the tops of the gables finished with sods, capped with a thatched roof which overhang at the eaves. Many people in the area still live in these houses, albeit they are modernised with slate roofs and all mod cons, but they still retain their charm, and importantly their warmth.

Today is Earth Day, the 50th anniversary in fact, although of course every day is Earth Day. We seriously must remake our relationship with our Earth home, and to nourish Earth, not deplete it; To respect Earth, not dismiss it; To celebrate Earth, not blame it.

Rachael Carson in her acclaimed 1962 Silent Spring wrote “No witchcraft, no enemy action had silenced the rebirth of new life in this stricken world. The people had done it to themselves.”

Day 18- Hazel

As a follow on from yesterday’s post about mud houses, hazel seems like an appropriate tree to muse over, as it was often the “wattle” in medieval wattle houses in Ireland. Surviving examples of wattle houses are recorded in 1946 in County Monaghan, that were built in the 19th century if not before.

Its leaves are unfurling and spreading out now, giving a gorgeous green softness as the light readily penetrates them. Because they can readily grow from a stump, hazel trees are often coppiced, or cut right back so that new straight shoots grow up as hazel rods. Many a hazel rod was used as wattle or as a pea stick.

The Irish for hazel is Coll, which also had the meaning of chieftan. Interestingly the English name Hazel derives from an Anglo-Saxon word meaning authority or kingship. In early Irish law hazel is classified as a Noble of the Wood – an Airig Fedo.

The yellow lamb’s tails or male catkins can have 4million pollen grains, and the tiny female red flower sits close to the twig and can be hard to find, but worth a search. After pollination these will be the tasty and nutritious hazel nuts, an important food source in Ireland from the earliest times.

It is regarded as a good protector against evil spirits and hazel sticks are often used by water diviners to find water. Hazel is found in older hedges, and old woodlands in Monaghan and indeed in some placenames too. Carnquill, Tedavnet is Carn an Choill, the Cairn of the Hazel.

Day 19- Marshy placenames

Townland names in Ireland are a sort of risen cake, for which the ingredients can be discerned but a flavour, hence an ingredient can be missed or mistaken for something else. For they have been baked for 2,000 years, some of them, and evolved through various re-namings, anglisations and land-use changes so that the feature for which they were named may be long gone.

A felled woodland. A disassembled cairn. A drained wetland. A fallen church. But still, much remains, and that alignment of place and name still, carries optimism for our landscape.

Marshy or boggy townland names are found across the country and are very common in Monaghan, not surprising when one considers the drumlins peaking above the soggy bottoms of the wetlands.

Annacramph is Eanach Creamha – fen of the wild garlic, a plant coming into flower now. Wild garlic is also called Ramsons and likes a nice rich calcareous damp soil. Plants that were useful food sources, like garlic are often found in placenames.

Annaroe is Eanach Rua, translating as Red Fen, likely due to the presence of a species of Sphagnum moss which has a vivid red colour and grows in fen habitats.

Irish words for marsh include riasc, seascann and currach. Sheskin is An Seisceann which is a sedgey bog or marsh.

Another evocative townland name is Drumhillagh or Droim Shaileach or Ridge of the Willow. Willow of course is a well-known tree of wet places and will grow in the most waterlogged of conditions.

The Irish for Willow, Saileach is very close to its latin name Salix. The Sally rod was once a tool to be feared due to its pliable nature, an easy whip across many any outstretched palm at school or home. But this was a misuse of a lovely and useful tree, which was often planted as “Sally gardens” so to avail of its many positive uses.

Willow has a wonderful fragrance when steeped in water and used for basket making. In early Irish Law willow was classified as a commoner of the wood. We are all willow. Each of us are commonage keepers on this planet – if one person takes too much, it impacts on everyone else.

Day 20- Cow Parsley and other Bό flowers

Seemingly out of nowhere, Cow Parsley appears on grassy verges in late Spring, a showy triumphant umbellifer with lots of small white flowers waving lightly in the breeze. The combination of their leafiness and their lacey tops has resulted in their alternative name “Queen Anne Lace” but in Monaghan, even though we are proud custodians of Carrickmacross Lace and Clones Lace it doesn’t seem to be a common name here.

It is Peirsil Bhό as gaeilge, and it is apt as it flourishes on the Bόthar (road) edges. The origins of the word Bόthar derives from a path wide enough for cows to pass each other. Bό is the irish for cow. Cow Parsley grows very fast. With its hollow stems and leafiness, it shades out the earlier spring flowers very quickly before it has its moment in the sun or is chomped by livestock on their way to market, or more likely nowadays is chomped by a mower. It dies back very quickly in any case to be replaced by the next wave of summer flowers wanting to show their wares.

Another Bό plant out at the moment is the Cowslip, the nodding head relation of the primrose, with whom it sometimes hybridises to create false oxlips. Cowslip is Bainne Bό Bleachtáin which is Dairy Cow Milky flower. It was rubbed on cow’s udders in the past to help them produce milk. There’s often something in a name.

Day 21-Stepping stones

How we cross streams and rivers is scarcely remarkable to us now, unless perhaps we are on foot and can lean over the parapet walls of a bridge and look down to see the water below. As a people on foot, we travelled by “shanks mare” and knew special crossing places. Áthanna are fords or stepping-stones, a shallow part of a river, reaching from bank to bank augmented by stone and/or timber, where people, animals and vehicles crossed.

The ford at Aclint Bridge, had a famous meeting in 1599, where the second Earl of Essex met with Hugh O’Neil, the Earl of Tyrone. This is between Garlegobban, County Monaghan and Essex Ford, County Louth. The restored Essex Ford forge sits prominently on the roadside, waiting for the horses that are only ghosts now. Aclint is Béal Átha Claonta, mouth of the sloping ford.

Átha finds its ways into more placenames, at least twenty-nine places in Monaghan such as Béal Átha Beithe, the ford at the mouth of the birches, or Ballybay. Here the Dromore River links two lakes either side of the ridge where the town now sits, which is the perfect wetland habitat for birch trees still. Béal Átha an Iúir or Ford at the mouth of the Yew trees or Ballynure also speaks of trees. The majestic Irish Yews must have been a wonderful sight. They were much revered and important tree in early Irish law, and often planted to mark church boundaries. Yews have a very long life, many hundreds of years, and traditionally considered to be symbolic of eternity.

The term stepping stones emerged in the most significant European nature legislation in 1992, where the directive asked Ireland and other member states to encourage the management of features of the landscape, such as rivers, field boundaries, small woods and ponds for their function as stepping stones for “migration, dispersal an exchange of wild species”.

In other words, we must allow nature to function properly as a system with many parts. Increasingly, almost thirty years later this small paragraph in the directive is realised to be fundamentally necessary. Nature will not survive unless it can be everywhere, all its cogs turning together, all the jigsaw pieces together forming one picture with us as part of that picture.

Photo – Yew tree at Crom, Co. Fermanagh.

Day 22-Thorn quicks to a hedge

Hawthorn, a plant almost oblivious to hardship, is part of the thorny rose family. Now it is in leaf, we will soon see it blossom with its foam of May flowers, unless it has been trimmed too soon or cut down to a quick. If hawthorn is not allowed to flower, then it cannot produce the shiny red haws on which the birds so depend in the autumn.

Most of our hedgerows have hawthorn, or whitethorn as their staple, stable-ising structure – their spiny interlocking branches form a great weft and weave supporting other weaker plants to climb and ramble such as dog roses and honeysuckle. In the summer evenings, the wonderful scent of honeysuckle will stop any walker and the moths in their tracks, as the plant waits till then to send out its fragrance so to attract its pollinating insects. Bats need decent hedgerows to forage along in the evenings too, catching midges and moths along its route. Walking along a hedge which luckily has some height and dappled shade will now bring you close to the speckled wood butterfly. It spins around with its mate in a flurry of aerial dancing in its chocolate brown and cappuccino colours.

Hedgerows were planted in the 18th and 19th century for farming, for shelter, control of livestock and to mark land holdings and townland boundaries. Some are remnants of older woodlands. In wetter places, they have a drain on one side, the digging out of the drain itself formed the material for the earthen bank upon which the hawthorn quicks were planted. Gloriously often called the sheugh, pronounced shuck or simply the ditch.

The Irish for hedge is sceach and hawthorn is sceach gheal. It was always thought unlucky to cut lone fairy bushes – those singular whitethorn trees, or to bring it indoors. Considered to be powerful tree, the Maguire chiefs were inaugurated at a thorn tree at Lisnakeagh fort in Fermanagh. Lios na Scéithe is fort of the whitethorn tree.

The more species in a hedge, the better for wildlife, for they are the conduits through which nature survives in the countryside. Birds, especially. What would our days be without birdsong? This is one of the reasons why it is strictly prohibited to cut hedges now, except for a limited number of exceptions. The new awful fashion to treat hedges as simply gappy dentils – low, waist height, only sticks really must be revisited and resisted. As one of the farmers said at the 2019 Farming for Nature awards, ‘if whitethorn is not allowed to bloom, you don’t have a hedge you just have a bundle of sticks’.

Day 23- First Fruits Gothic

It is worth casting an eye on church buildings afresh, for they are longstanding bystanders to all sorts of comings and goings over the centuries. All sorts of people, clothed in various fashions of the day, travelling by foot, horse, carriage, bicycle and car have been through the doors on occasions, sad and happy.

In 1711, Queen Anne established the Board of the First Fruits to build and improve churches and glebe houses in Ireland for the established state church, the Church of Ireland. Apparently, she was persuaded by the giant of Gulliver’s Travels – Dean Jonathon Swift. Perhaps he had a little self-interest in the matter and may have been feeling the chill in a draughty glebe house. Someone said, “Many are cold, but none are frozen”.

Many small rural and some urban churches were built with assistance from the board, often with a common feature of a small, sturdy, square west tower with pinnacles on top. Spires were more expensive add on and required a wealthy benefactor or congregation. The architects had a fine eye for a prominent and aesthetic setting for these new churches, moving away but often not too far from the old medieval church sites.

Newbliss Church of Ireland is one of these First Fruit churches. According to architectural historian Kevin V.Mulligan, it is “an exacting small church, dramatically sited against a hillside on the edge of town with a tower bristling with needle-like pinnacles”. Donaghmoyne, now disused sitting on top a good steep incline also with its gothic hall and tower is also near the site of an ancient church. The Annals of Ulster record that in 832 the shrine of St Adamnan was taken by the Vikings. A shrine is decorated fine metal box containing the saint’s relics or bones. It was apparently on tour at the time.

The Board of the First Fruits lasted until 1833, when it was dissolved.

Have a look for some pinnacles, they are not so rare as needles in the haystack.

The photo is of Crossduff Parish Church, close to Lough Egish, a small chapel with its tower and pinnacles, beautifully surrounded by beech trees.

Day 24- Bell-houses

Patrick Kavanagh felt “the God of imagination waking in a Mucker fog”, which perhaps St Daig, the great maker of bells and shrines also felt, albeit centuries before, but the landscape remains silent on this rumination. St Daig of Inniskeen was a renowned metal smith or blacksmith and described as a “great artificer”.

Handbells, of sheet iron or cast bronze, so quite weighty and sonorous, were common in early medieval Christian Ireland and over 70 actual examples survive. They may have been used as part of processions into and ascending round towers. Cloictheach (Bell-house) is the Irish for Round tower, but no remains of actual belfries or large bells remain to provide definitively how this function was undertaken. So, it is possible that the monks rang the hand-bells from the top of the towers as part of ceremonies or to call people to prayer. Many of the depictions of monks from this time, show these holy men holding a hand bell.

The round tower at Inniskeen is much stunted now – it is hard to imagine it at its full height but it once was a thriving busy monastic site. Clones round tower is a more imposing structure still, only missing the very top capping, but hidden from view at the back of town.

Laobhán, one of Patrick’s smiths was the founding saint at Killevan, Cill Laobhán. He may have forged bells as well as tools and horse bits. Blacksmiths were fundamental to all societies, which is why they are specifically mentioned in the old annals. Monasteries, church settings, and farms all needed their fires lit to keep the societies functioning.

The photos are of Clones Round tower and a discoid headstone from Killeevan with a depiction of a hand bell amongst the symbols of mortality.

Day 25- Purple Vetchlings

These pea family members are scrambling through the lower grassy parts of hedges now, using their teeny curly tendrils to elegantly pull themselves up and wind themselves around other plants. Even though they rely on others for support, vetches give back to their neighbours by fixing atmospheric nitrogen into the soil. Vetches have a symbiotic relationship with nitrogen fixing bacteria; this aids its own ramblings and that of its neighbours. Very neighbourly.

They have little purple flowers, and pairs of leaves reaching up ending in tiny tendrils. Bush vetch or vicia sepium literally means vetch of the hedges as sepes is of a hedge. In Irish the vetches are Peasair vicia.

Later in the year, little brown or black pea pods will develop on the vetches.

Vetches provide important source of pollen and nectar for bumblebees, our little fluffy piled batteries of nature, which are in decline and need a variety of flowers and plants from early spring to ensure their survival. It seems that bees see the colour purple more easily than any other colour. Pollen is their protein and nectar their sugar.

Today 30 April is Poetry Day Ireland and so to quote some lines of Patrick Kavanagh…

Dead in a Ditch

(To Hilda)

Unless you come

I shall die in a ditch,

Poet dead in a ditch.

There will be no bluebells there,

Only the vetch

Smelling of death

Weeds around me,

The mud of hooves

That prance there

Falling over my eyes.

Patrick Kavanagh 1945

Day 26- Megalithic Court Tombs or Giants Graves

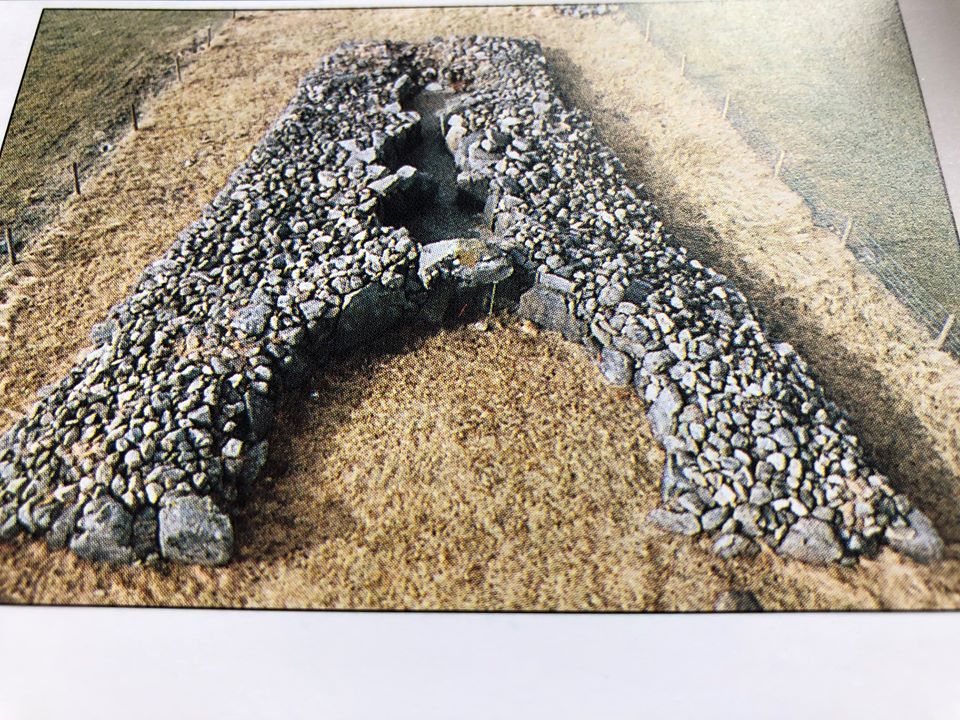

Surviving through 6,000 years of immense cultural and ecological changes is no mean feat, yet at least 19 examples of court tombs remain in Monaghan. Part of megalithic tombs types (mega – large, lithic – stone), these are often called Giant’s Graves on the old maps and in memory.

Court tombs have U-shaped open roofed court-yards set in front of a long covered gallery or cairn. Inside the gallery there is often 3-4 or more rooms or chambers into which cremations were placed. The tombs were used over centuries. The old burials were often pushed aside to make room for new ones. The courtyard, which was flanked with large standing stones is thought to have been used for long forgotten rituals, wakes maybe, fires perhaps, to do with the ancestors held within.

A tremendous example of a court-tomb was at Cashlan, long since destroyed but it is worth the effort to read the 1841 and 1897 reports on the National Monuments website, and to see the plan of the chambered cairn that was drawn at the time. It is part of the collection of these tombs in the Newbliss area. Its reference number is MO012-080

Aghnafarcan or Ath na Farcan, Ford of the Oak, or alternatively Achaidh farcáin, meaning field, has a giant’s grave called ‘Minnavarmore’. Recorded in the Irish Folklore Commission collection is a folk tradition of a Scandinavian giant called Manowar, who came here to kill Finn McCool. Fearing the giant, Finn disguised himself as a baby, and bit Manowar on the finger. Naturally enough, if this was the baby, no doubt he thought, what is that father like? In any event, the Scandi giant tried to leave but mysteriously dropped dead, and hence ended here in Farney.

In absence of access to photographs at the moment, here is an outline of a court tomb from nearby County Tyrone.

Day 27- Orange tip Butterfly

This striking and beautiful butterfly has a dark side, and by that I refer not to its green marbling on the underwings, which is in fact made from black and yellow scales, but to its cannaballistic nature. Yes, that is right, the caterpillar will eat any eggs and competing caterpillars it finds on the same plant.

Orange tip butterflies are attracted to cuckoo-flower or lady’s smock, the mauve delicacy of the cabbage family, which has a circle of dainty flowers topping off a soft stem. Cuckoo-flower favours meadows and verges with low nutrients or low fertility and low stocking density so less grazing.

Its latin name Cardamine pratensis means watercress of the meadow, and the butterfly complements this, it is named Anthocaris cardamines or Barr Buí as gaeilge. Yellow tipped. Only the male butterflies have the orange tips though, so the sexes are easy to tell apart.

It lays its wee eggs on the stalks of the cuckoo-flower, which are at first a pale green changing colour to a vivid orange. The caterpillar is green with a white line along each side and will eat the developing seeds and fruits of the flower and other younger caterpillars. Survival of the fittest rules the roost.

An old Irish poem praises the cuckoo-flower (Bioloar Gréagáin), where it grew in Gleann Ghualainn at the time of the warrior fianna. It was deemed to be good for nervous afflictions like hysteria. Considered to be a flower of the fairies, whose magical powers are to be respected, it is not to be picked and brought into the house for fear of been struck by lightning. Its name cuckoo-flower may be because it blossoms around the time of the first cuckoo calls. The alternative name Lady’s Smock may derive from its wee circlet of flowers which look like smocks blowing in the wind as they are hung out to dry.

This weekend the National Biodiversity Data Centre are asking us to record sightings of the Orange-tip butterfly. You can find them easily on twitter, on Instagram or their wonderfully informative website www.biodiversityireland.ie

Day 28-Home fires & vernacular homes

In the vernacular or traditional houses in Monaghan, till after 1600, houses had a free-standing hearth with a simple smoke-hole in a central position of the roof ridge, and the pot hung from the central roof timber. Very smokey and dark.

The innovation of a hearth and chimney style houses from the 17th century, must have brought great clarity and relief from the smoke. A canopy made from hazel – wattle and daub, or wickerwork was positioned on the gable wall of the house over the hearth. This was a big pyramidal flue essentially, which was plastered with mud and straw and then limewashed. Its top is recorded as protruding above the roof ridge, was obvious from the outside – a kind of chimney.

The big canopy was supported on a timber that ran across the width of the house, supported on the side walls. Flanking the hearth was often niches called keep holes, sometimes with doors, used to keep things like salt dry or for other bits and pieces, pipe and sewing are recorded. The blacksmith was able to forge cranes on which to hang an assortment of pots and skillets. Some of these cranes were decorated, a little flourish of pride in the new arrangement.

The canopy and the brace beam on which it was supported allowed the homes to have a half-loft either side of the hearth. Warmer places for sleeping than before. Often called the thallage in Ulster, this seems to be anglisation of the word tailleog meaning loft.

Day 29- Herb Robert

This is a gangly, leafy plant when it is growing in spots that suit it, but it is a tough cookie and will grow in suppressed conditions like cracks in pavements and on stone walls but looks dried out and stumpy there. In all places it has gorgeous dainty red-pink flower, and often red stems. In Autumn, the leaves can turn pink or red. It is in the hedgerows now.

Herb Robert is an unusual name, and thought to be a corruption of Herba Rubra – Red plant, not Robert Plant, although wouldn’t it suit a Led Zeppelin band member? It is a species of crane’s bill, or geranium, and as gaeilge it is Crobh or also Ruithéal Rí.

Medicinally, its bright red stems were used to cure cattle from red water fever – fire fights fire. It was also used to staunch bleeding, treat kidney problems and sore throats.

When its flowers hang it is a sign of bad weather, and do not bring it indoors for it has an unpleasant smell and hence another name – stinking bob.

Day 30- Rowan or Mountain Ash

This commoner of the wood, according to the brehon law texts, is quietly bursting into flower now. Minute umbels of creamy white flowers erupt from tight little pearly balls, sitting proud above the toothed leaves. Pollinators, especially bees and flies are attracted to its flowers.

Later in the season, there will be clots of rowan berries in their place, much revered since ancient times and found in old stories and poems. A Seamus Heaney translation of ‘Sweeney Astray’, a poem about Suibhne Geilt, king of Dál Araide, one of the kingdoms of Ulaid (Ulster) finds that-

“scarlet berries clot like blood

On mountain rowan”.

Birds, especially thrushes like their berries, but they do not digest the seed within, so new seedings are propagated by being passed in their droppings.

Its scientific name is Sorbus aucuparia. Its Irish name Caorthann, refers to caor, which means burning flame. Rowan is associated with the month of May, and the first smoke from a chimney on a May morning should be from the fire of rowan. It was used to protect cattle and was tied to their tails to save them from fairies. In some old poems it was referred to as the fid na ndruad, the druids tree. They apparently used it for divination. Spells.

Day 31- Waterwheels

It is a clever and simple invention to capture the power of water, by spilling it into cascading buckets on a wheel, making it turn cogs and shafts. The industrial process of casting iron, pouring liquid iron like lava into moulds enabled the combination of timber and iron to create waterwheels.

Fred Hamond conducted an industrial survey of mills some years ago for the Monaghan Heritage Office. He identified 193 locations where mill once operated in the county, 165 of which used the renewable energy of water to power them. The water was abstracted by constructing a weir across a river or stream to divert some of it, so that it arrived at the waterwheel at a higher level than the river. The largest waterwheel, 25ft in diameter, in Monaghan was at Tullygillen Corn Mill, a few miles south of Monaghan town. Locally called corn, oats grew better in wet Monaghan soils than wheat so small corn mills were more common.

Neal Doran (1849 – 1937) of Derrynoose and Doohamlet, penned songs of local interest, people and places, that were recently compiled into a book by John Makem. Here are the first two verses of “The night of the big wind” –

In the year eighteen hundred and just sixty-four,

The likes in this country was ne’r seen before

The wind and the divil they made combine

And on that day they left nothing behind.

The flax over hedges and ditches was blew,

And besides all the stooks in the fields they were threw

The corn was threshed into straw on the hills

No business at all will we have for the mills.

The photo is of New Mills, Kilcran, outside of Glaslough. This fine mill has an internal waterwheel.

Day 32- Mostly known as Bulrush

You will recognise this plant immediately, no matter what its’ given name, by the tall sausage shaped heads, vegan of course. The brown shaped sausages are actually a collection of teeny flowers that make up the inflorescence. Variously known as bulrush or reedmace it is one of the tallest grasses that grows around the margins of lakes, in canals, and transition mires (which are a stage in the development of lake to fen to bog). Its scientific name is Typha latifolia.

The underground rhizomes are edible. Evidence of preserved starch grains from bulrushes have been found on grinding stones in Europe 30,000 years ago. The green long flat leaves have been used in cooking as well, and the fluffy seed heads were used for lining baby baskets in Finland.

It flowers in the spring and the male and female flower clusters are borne on the same stem. Reedmace produces huge amounts of seeds, which are equipped with tiny parachutes to help them disperse with the wind. The photo taken at Killyboley Lough shows the fluffy seed head, honestly looking very otherworldly.

It is no surprise then, that as gaeilge it is Coigeal na mBan Sí, the fairy woman’s spindle. A spindle is a slender rod used in hand spinning to twist and wind wool or flax. Possibly she was winding thread to weave some class of invisibility cloak, as used more recently by the well-known wizard Harry Potter.

Day 33- Gothic Monaghan

Today for Heritage Happenings we are launching our film ‘Gothic Monaghan’ online. Filmed three years ago, on locations in County Monaghan with a few shots from France, this film looks at the fashion for gothic architecture in the landscape of Monaghan, Ireland and traces the evolution of the style through old church ruins and abbeys. Presented by architectural historian and author Kevin V. Mulligan and heritage officer Shirley Clerkin, directed and filmed by Dara McCluskey, its’ premier showing was at the International Clones Film Festival in 2017. The film was funded through the Heritage Council and Monaghan County Council.

Locations include Magheross Old Church, Killeevan Old Abbey, Clones Round Tower graveyard, High Cross and wee Abbey, Lough Fea House, Bessmont House, St. Josephs Carrickmacross, Adragh Church, Cahans Presbyterian, St. Patricks Church Monaghan, St. Macartan’s Cathedral and many more.

Day 34- Lost Book of Drumsnat

Where the lost things go?

In the latest Mary Poppins film Emily Blunt sings about the lost things. Two of these particular lost things, the lost book of Drumsnat and the chest of gold fallen to the bottom of the lake would create more than a musical response if discovered.

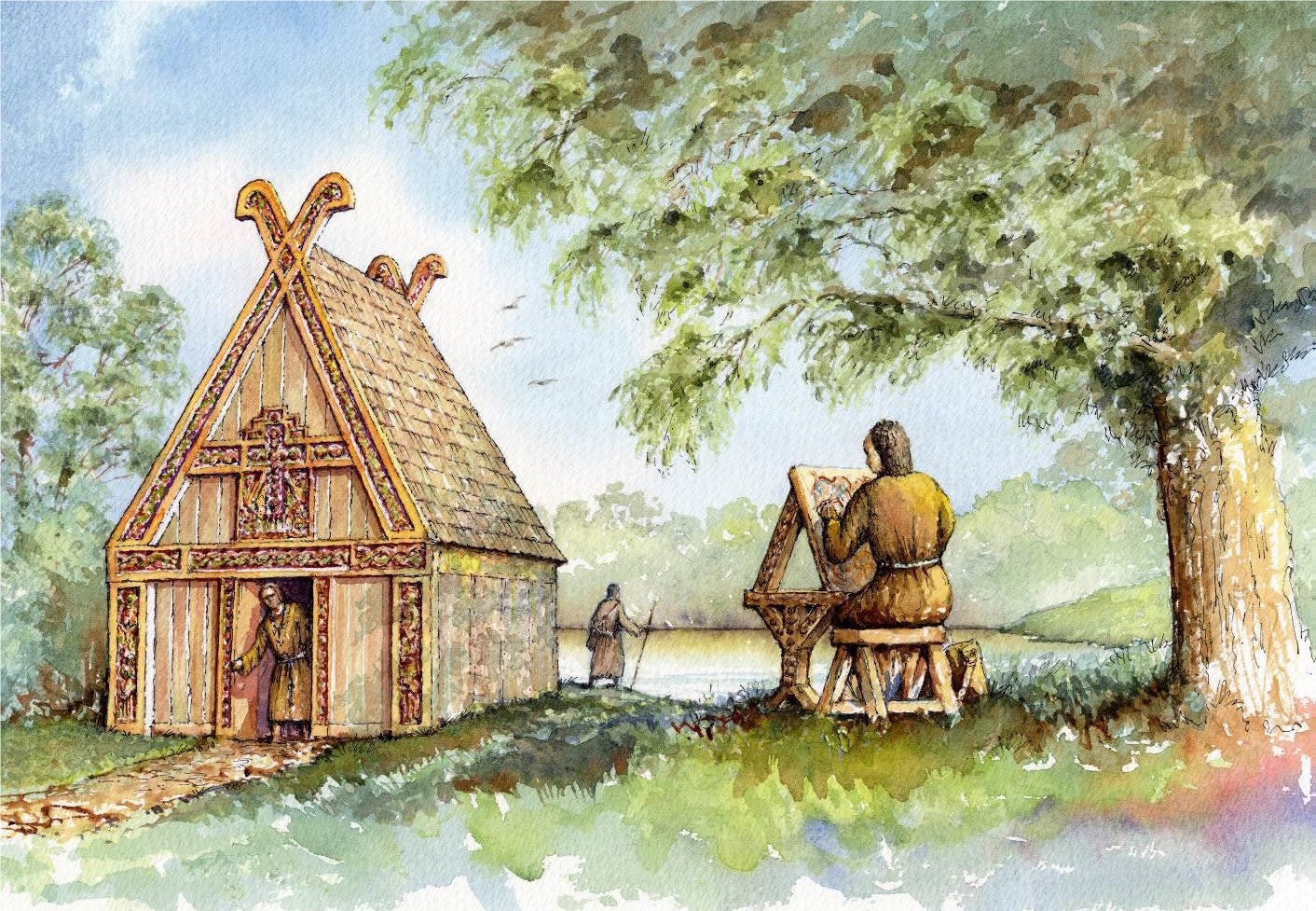

Drumsnat Monastery, between Monaghan and Clones, was founded by Molua MacOche of Kyle, Killaloe and of Drumsnat in the 6th century. He studied with Comhgall at Bangor and performed many miracles for which is was named “Servant of the three nines”. He died in AD 609 aged 55.

Mullanacross, Mullach na Croise, Hill of the cross, where the monastery is said to have stood, now has an old graveyard with some interesting stone markers, and more recent headstones, still overlooking the pretty Drumsnat Lough. It is called Drumsnat, Droim Sneachta, Hill of the snow due to the sign of snow covering the landscape un-seasonably in June and on that basis Molua established the monastery here.

The lost book of Drumsnat, Cin Droma Sneactha was written here in the 8th century, which is the oldest known manuscript to contain Old Irish Saga material. These epic sagas or stories were highly complicated prose and poetry brimming with tragedies and drama. The Cin is referred to in many later books, but alas it has not been found.

As for the lost gold, well it is said in the folklore that when St Patrick banished the serpents, a great chest of gold fell into the bottom of Drumsnat lough. A serpent has been coiled around it guarding it since.

The drawing is a reconstruction of early timber church at Drumsnat, overlooking the lake by Philip Armstrong. This was drawn for the soon to be published conservation plan for Drumsnat Monastic site, by IAC for Monaghan County Council Heritage Office.

Day 35- Purple blues – the bugle and the dead nettle

Two little purple gems of the woodland and verge edges are peeking out now, adding that purple dash of colour that is so perfect amongst the green.

The Red Dead Nettle is related to the mints, and non-stinging as its name suggests so you can grasp it without fear. Dead nettle has a square stem and an unusual flower shape, a sort of hooded tube in purple, and the leaves can also have the purple tinge. Its Irish name Neantóg Mhuire, Mary’s nettle.

Bugle is slightly bluer, and its grows as tiny turrets of dark colours in drifts at the edges of woodland or on old verges. It likes damp but limey conditions. It is Glasair choille in Irish was used in the past as a cure for ulcers and gangrene.

Look out for them, they are pleasant to see and to know. Prepare to impress others by grasping the dead nettle.

Day 36- Signal Cabins

The Ulster Railway started life in 1837, initiated by local businesses who wished to join Belfast with the linen milling centres around Armagh. By 1876, many lines had been completed through the complicated topography of the wetland – drumlin south areas into Monaghan and Cavan, line guages were standardised and the Great Northern Railway company incorporated. In County Monaghan there were fourteen railway stations.

Signal boxes were an advance in safety for railways and integral to the busy transport infrastructure. They allowed rail staff to safely observe nearby trains and to control their movements. The boxes were designed to a generic standard and could be sized up or down depending on the levers required inside, without compromising their aesthetics. All was considered, type of brick, timber for windows, bangor slates for the roof. They are instantly recognisable as to their function as a result.

The photo shows the rebuilt Glaslough signal cabin, reconstructed faithfully to the original design by the local community. Railway stations varied in their designs, some were classical, italianate or in Glaslough – gothic, but the cabin boxes are a pleasing punch of replication except for the name of the station above the door.

Sadly, the GNR lines in County Monaghan closed in 1957.

Day 37-Private sculpture or public art?

There are a number of Black Islands in County Monaghan, but only the one with a life-size white sculpture. Amidst the former Dartrey Estate, situated on the island is a grief-stricken group of marble figures dating from 1774, housed in their very own classical temple.

The entire ensemble was commissioned by Lord Dartrey following the death of his young wife Anne in 1769. The temple is just that, it is not a burial place or mausoleum, but a memorial sculptural set, designed to be visible from his house, a private yet public declaration of love or maybe to record in stone his own grief. The square classical temple box in which it is housed was designed by James Wyatt. It has no windows, one light source only from above through the domed roof.

The marble figures and funerary urn are of Lord Dartrey himself, his young son and a beautiful angel with large feathered wings, gracing a cloud. The entire arrangement is most affecting. The sculpture was designed and carved by Joseph Wilton, one of the founding members of the Royal Academy.

After the estate was dismantled, the temple and sculpture fell into a ruinous state in the late twentieth century. One of the most amazing aspects of the story is the rescue. Through the valiant efforts of the Dartrey Heritage Group, the temple and Wilton’s grieving figures were rescued and restored in the early 21st century. The light shines on them once more.

The photo shows Noel Carney from the Dartrey Heritage Group at the sculpture in 2015.

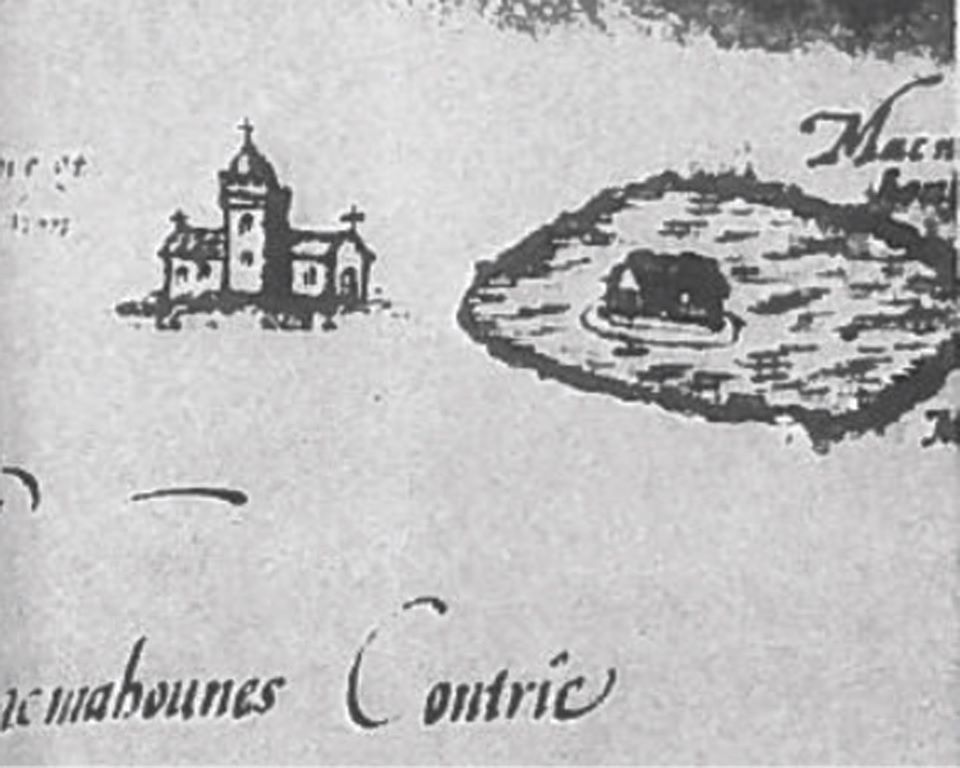

Day 38- Crannógs

A high proportion of our ancestors in the drumlin-wetland landscape were water people, living on artificial islands on lakes. Social distance by means of a watery protection, and a timber palisade which generally surrounded these sites.

Crannógs were built up with layers of stones, gravel, peat, brushwood, upon which the dwelling was built.

Archaeological investigations have shown that there was a wide time period of construction, from at least the bronze age to post-medieval times. Up to a few hundred years ago, therefore. Dendrochronology, or dating analysis of the timbers suggests a major period of building during the 6th and 7th centuries.

In Monaghan there are almost 90 recorded examples, in which antiquarians of the 19th century became interested when the agricultural drainage schemes dropped the water levels in lakes making the sites more visible and accessible.

E.P. Shirley of Lough Fea, Carrickmacorss investigated the Monaghan crannógs of Drummond Otra in Loughnaglack, Drumbo in Rahans Lough and Monaltyduff in Monalty Lough.

Artefacts from crannógs show that the sites were of high status, with evidence of metal working and crafts – bronze pins, knives and blades, thimbles, glass beads; tillage, commerce, music – harp pegs; food storage and fighting.

The St. Louis Secondary School in Monaghan town may be the only school in the country overlooking its own crannóg, that of the McMahons, now in the Convent lake, Mullaghmonaghan. This was MacMahons caislean or castle of MacMahon mentioned in 1492. The tops of four oak piles can be seen on the northern side still, and the boulder kerb can be seen beneath the water. Old maps and drawings show that once it had a slated house situated upon it.

The photo depicts part of the 1591 map of Monaghan showing Franciscan Abbey and Macmahoones house on the crannog, copied from the Historic Monument Viewer.

Day 39-Not so humble Bumblebees

Charles Darwin noticed that “humble-bees alone visit red clover, as other bees cannot reach the nectar”. Humble not bumble bees was an old name, not in use since world war two, and Darwin was referring to their long tongues which allow them to collect nectar from flowers that are closed into a tube.

Bumblebees are plump, fuzzy, stout flying bees with bands of colour making up their dense pile, their varying stripes a good aid to tell which species is which, together with their tail colours in Ireland of white, buff or red. They can sting but they have no barbs on their sting so can survive an encounter. Bumblebees form small colonies with one queen. There are 14 species of true bumblebees in Ireland, and 6 cuckoo bumblebees which as their name suggests don’t bother making their own nests but invade instead, kill the resident queen, lay their own eggs which are then cared for by the workers.

Bumblebees usually forage within 200-500m of their nest, generally an underground disused mammal burrow, but the new queens will travel from 1-5km away from their birth nest to establish their own colony.

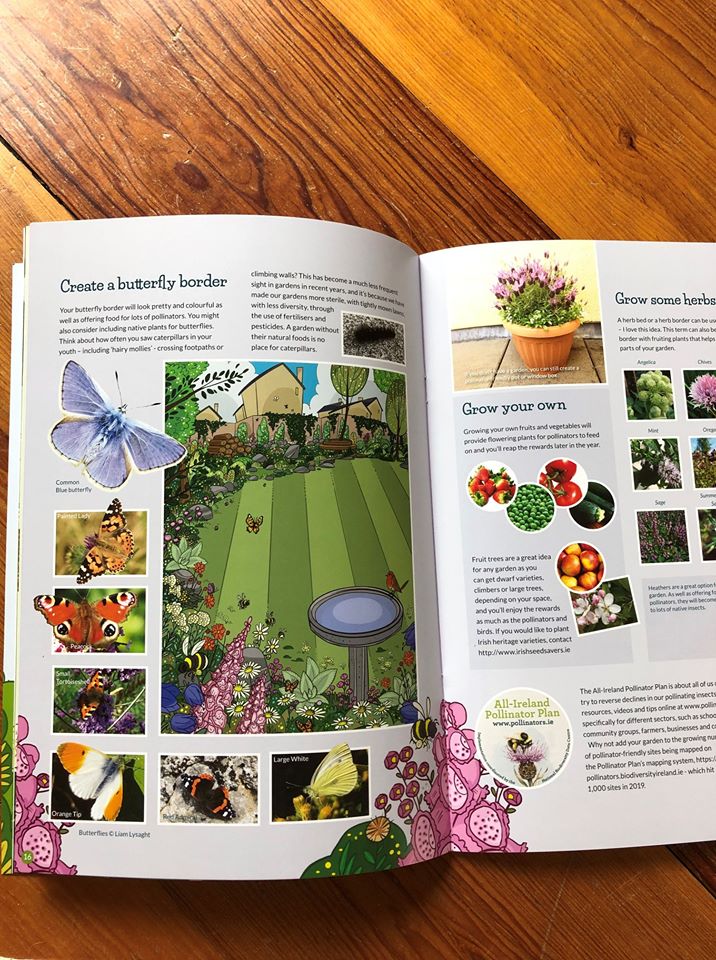

Sadly, due to habitat loss, pesticide usage and other human impacts one-third of all bees species in Ireland are threatened with extinction. As three out of every four wild bees is a bumblebee and we rely on them to pollinate fruit and vegetables this is very bad news. We drastically need to improve habitat, shelter and food for bumblebees and every little bit makes a difference. Check out the All-Ireland Pollinator Plan website for resources and easy things you can do for bees at pollinators.ie and check out Gardening for Biodiversity by Juanita Browne available online as well.

J.K Rowling is an admirer of bumblebees and named the headmaster of Hogwarts in the Harry Potter books after an old name for the buzzy fuzzy batteries of nature – Dumbledor – “one of his passions is music and I imagined him walking around humming to himself”.

Day 40: The majestic bird of the uplands – Hen Harrier

Initially, it was thought that male and female Hen Harriers belonged to two different species, so unalike they appear – a touch of the “men are from mars, women are from Venus,” but that is all sorted out now. They are a majestic, daring and protected bird of prey, found in the uplands, and on Sliabh Beagh – the upland plateau joining Monaghan, Tyrone and Fermanagh.

Their scientific name Circus cyaneus captures a part of their behaviour and personality, astonishing circular aerial acrobatic displays called sky dancing which the male performs to impress the female during courtship. She is hard to impress. The male rise high in the sky and then suddenly plummets to the ground in a series of somersaults, twits and corkscrews, to all intensive purposes seemingly bound to crash, when he halts his screech to the ground and rises upwards again. He can perform these dances for twenty minutes, a demonstration of stamina and daring.

The female though, can fly upside down and catch food mid-air that the male drops to her which she then feeds to the chicks.

The male is grey mostly with black wing tips, and the female is mainly brown. The food they expertly hunt consists of small mammals, and sometime small birds, and even occasional frogs. They breed from March to September, and it is crucial at this time not to disturb their nests, or foraging areas.

In Irish, Hen Harrier is Cromán na gCearch which could translate as Hip Hen, which of course they are. No other bird can undertake the flights of fanastical fancy of the Hen Harrier. We are privileged to have them in Monaghan under our protection. We have a duty of care to these birds and should not deprive the skies of their wonderful acrobatics.

Farmers are taking part in the Department of Agriculture scheme for the Hen Harrier in Monaghan currently and it is hoped that this project together with the interreg CANN project which also is working to protect Sliabh Beagh will be successful in their aims to restore nature.

Day 41-A noble of the wood and hedge – the Ash

The Ash tree or Uinnius or fuinseóg is the commonest tree found in our hedgerows. Always the laggard, they are finally leafing out now. According to the seventh century Brehon laws, where trees were ranked according to their usefulness, the ash was a one of the Airig fedo or seven nobles of the wood. The fines for damaging a noble was two milch cows and a three-year old heifer. Ash was useful for making hurleys (camán), spears, furniture, boats and other agricultural implements.

Sacred trees with a special place in the Irish landscape are known as bile. Bile Maedhbhs’ are said to have sprung up wherever Queen Maedhbh planted her horsewhip, which were made of ash. In addition, three of the five great trees of Ireland were ash. Bile Uisnigh at Uisnach, Bile Tortan at Ardbreccan (County Meath) and Craobh Daithi at Farbill (County Westmeath). Craobh means branch. Ash has stout grey twigs, with large leaf scars and black buds – easily recognisable along with its opposite pinnate leaves.

You will see it coming into leaf close to you now. Give the tree an appreciative pat or nod, as it’s an often overlooked species because it is ordinary and commonplace. We might only miss it when it is absent from our places. It is hoped that the Ash Dieback which is threatening so many of the trees at present, can be beaten by this noble of our hedgerows.

Day 42-The bright eye of the speedwell

These small four-lobed flowers, bright blue with a white eye in the centre are commonly found now along hedgerows, edges of woodland or in grasslands. Called speedwell, as they seem to wish good fortune to the traveller, they are also called Eyebright in ulster. They creep and wrangle their way upwards, with shapely leaves of about 1cm, and white hairs on their stems, ornamented with the startling blue flower, with two conspicuously draping long stamens.

Germander Speedwell, which is this specific species, is Veronica chamaedrys. The veronica species are so named, after the saint who wiped sweat from Jesus’s brow as he carried the cross. ‘Vera icon’ means true image.

In Irish, eyebright is anuallach, which possibly derives from humble-minded.

Day 43-Red Clover

The red globes of nectar rich Trifolium pratense is popping up now on road verges, fields and under hedges. Its leaves form a trefoil, like a shamrock, only larger and they often have a crescent pattern on them which bring a pleasing continuity across the leaves.

In Irish, it is Seamair Dhearg, and is one of the plants that was identified as the Irish emblematic “shamrock” in 1893, and again in 1988 when Charles Nelson repeated the survey.

Red clover is a pea species and can fix nitrogen in the soil and is very nutritious plant for livestock. Bumblebees too are very keen to suck the nectar out of its juicy pink-purple flowers. In the past, it had medicinal uses, as a cough remedy and for bee stings.

Clover appears as a symbol of prosperity and fertility of the land in early Irish myth. A story in the Dindshenchus describes how Tailtiú cleared rough ground until it became a plain blossoming with clover. She died from her labours, however, and a fair was held every year to mark her clover meadow, at Teltown, Co. Meath.

Day 44-Gate lodges

Once there were well over two thousand of these porters houses in Ulster, built to manage the entrances to the gated estates and as houses for the porter and his family. Well over half of these are now demolished or fallen into complete ruin. In contrast the larger house contained within the walls, the gate lodges were visible to all, a hint of what was to come inside the estate and a contrast to the vernacular small cottages built by the rest of the population. The divisions in society were maintained through architecture.

J.A.K. Dean describes them in his book Gatelodges of Ulster –

“In their size, style, placing and relation to other buildings they have much to tell us about their owners and about those who were expected to occupy them. Sometimes they heralded the style of the big house they shield. Occasionally, they were an architectural experiment, a test of style. Sometimes they were a remnant of an older style after the main house was remodelled.”

They were generally positioned at the gates, neatly behind the wall, or even as part of the wall itself, carefully thought out as one ensemble. These buildings are a valuable part of our social and architectural heritage, wonderful to see them in re-use as holiday lettings, offices and best of all as neat compact homes.

St. Macartan’s Cathedral in Monaghan finished its magnificent gates and screens with a victorian gothick gate lodge in 1884 by William Hague, the architect who completed the building of the cathedral after J.J. McCarthy died. Images of St. Macartan and St. Dympna, together with a bishops’ hat grace the stonework.

The Blayney Demesne originally had four gate lodges, three of which remain. The West Street lodges of 1860 are currently undergoing a phased programme of restoration by Monaghan County Council. The smaller lodge is now in use as office and community space, and the opposite larger lodge will be a new library for Castleblayney. Both beautifully frame the lime avenue to the main house and lake.

Castle Leslie in Glaslough had 6 lodges originally, all of which remain and according to Dean are “the most important and varied series of porter’s lodge buildings in Ulster, if not in Ireland”. They were all built within 75 years from 1800 – Gothick entrance (1812), Cottage Orné (1840), Tudor Romanesque entrance (1845), the Scots Baronial entrance on the main street (1875) and the Jacobean Entrance of (1878).

The photos are of the Scots Baronial entrance and the Jacobean Entrance to Castle Leslie, and the West Street lodge of Castle Blayney.

Day 45-World Bee Day

Today 20th May is World Bee Day.

Bees are vital insects which pollinate wild flowers, shrubs and trees, and also as cogs in the wheel of the agricultural and horticultural industries who rely on these largely unsung heroes. Their intrinsic qualities, buzzing, flitting, hovering behaviours and stripey bands of colour are just as important. They do not have to be useful, but they are, it is enough to simple be a bee to be a valuable member of It is no wonder that their appearance is often mimicked by other species like the hoverflies. They say they there is no higher form of flattery than imitation. But we should not want to be a society that wears bee costumes to fancy dress parties while the real things flounder due to our negligence.

Over one-third of bee species threatened in Ireland, yet we can decide to make a difference on our patch of the planet. Every garden is important and can be a place where bees and other wildlife are welcome.

If you mow your grass less often, plants like clovers and dandelions will grow – great food for bees. Or if you leave longer grass areas around the edges of your garden for example, you will provide them with shelter and food. Native hedgerows abounding in hawthorn, and native trees like willow all are part of the solution. It is clearly important is not to poison these little creatures, so please avoid using pesticides and weed killers. You can also plant herbs and flowers which attract bees.

The National Biodiversity Data Centre provide useful information on their website for pollinators at pollinators.ie. There are great animations, lists of suitable plants and simple ways to improve the life of bees in your garden.

Happy Bee Day.

Day 46-Biodiversity Week

Biodiversity – our life support system

Nature’s own music. Birdsong. Hum of bumblebees. Dashing screeching flight past of swifts. Dandelion clocks floating past on the air. Fragrant boughs of hawthorn. Glut of tadpoles. Steadfastness of oaks. Soggy bottom of sphagnum moss. Dragonfly nymph emerging from water to go out on a wing. Caterpillars transforming to butterflies. Patterned colours of their wings. Hedgehogs snuffling. Foxes silently brushing past.

Although biodiversity is a big scientific topic, we can think about it in endless ways, and why not consider it through the lens of wonder? If we were to create a magical place to live, would it be concrete all about with bowling green lawns, silent except for the noise we make, colourless except for the dyes we mix?

Biodiversity is all about us, but it is in serious trouble because we have neglected to include our very own life support system in our decision making, failing to realise that our quality of life and livelihoods, and the equity of human beings is dependent on it. We must break the cycle of harm and disrupt the systems to create better ways of doing our lives.

Biodiversity is the variety of life on the planet and how it interacts with the natural water cycles and climate conditions to create ecosystems that provide habitats, and ecosystem goods and services. Goods like timber, healthy soil, raw materials for clothing, medicines – everything. Services like carbon sequestration, water filtration, pollination – everything we rely on.

This is Biodiversity Week. But everyday we depend on biodiversity. Take a first step and connect with the wonder of the nature this Biodiversity week. Find a quiet spot and listen to the sounds of nature about you. This is the sound of nature supporting your life.

We will have some biodiversity tips on this page all week.

Day 47- Switch for Biodiversity

We want to live more harmoniously with nature. There are some simple switches that can be made that will set us on that pathway. Always the best place to start is where we can have the most influence, and for most of us that is our own homes and gardens. Today is International Biodiversity Day, no better day to start,

Here are ten SWITCHES you can make to benefit biodiversity right now:

1. Switch peat moss or compost with peat FOR PEAT-FREE COMPOST. Ask your garden centre. Or make your own compost. This will help protect our valuable bog ecosystems.

2. Switch your weekly mow to LET YOUR GRASS GROW. Leave an extra margin around the edge of your lawn and cut it every 3-6 weeks, to provide shelter and food for pollinators.

3. Switch tap water in your watering can to WATER FROM A WATER BUTT. Rainwater collected from your roof is a good way to re-use water and be more economical with treated water.

4. Switch plants in pots for PLANTS IN THE GROUND. These need less watering.

5. Switch pesticides for NATURAL PEST CONTROL AND COMPANION PLANTING. (Carrot fly is distracted by the smell of rosemary and thyme, plant marigolds or lady’s mantle close to tomatoes, nasturtium beside broad beans). Encourage ladybirds to your garden to eat greenfly.

6. Switch chemical fertiliser for NETTLE OR COMFREY FERTILISER. This is made by soaking the plants in water for a few weeks and then diluting the resultant liquid with water. Areas of nettles and comfrey are super for pollinators – bees and butterflies, so a patch has additional biodiversity benefits.

7. Switch cutting hedges at waist height to LETTING HAWTHORN HEDGES GROW TALL AND BLOSSOM. Vital for pollinators and will bring a wonderful sight and smell to your garden.

8. Switch tidying up to BUILDING A LOG PILE. Great spot for hedgehogs, bugs and beetles. The garden is not a place for Marie Kondo’s house tidying approach!

9. Switch planting the same plants everywhere to PLANTING VARIETY. This will protect your garden from being overrun with any one pest or disease, and bring more wildlife to your place.

10. Switch social distance for HUGGING A TREE.

Monaghan County Council has some copies of GARDENING FOR BIODIVERSITY available. This wonderful publication from Laois County Council, supported by the Heritage Council and the Heritage Officers is written by Juanita Browne and illustrated by Barry Reynolds. It is wonderful, and full of fantastic ideas for your garden. If you would like one to be posted to you, please email shclerkin@monaghancoco.ie and we will arrange it.

Day 48- Biodiversity for Birdsong

In her 1962 book Silent Spring, Rachael Carson worried that a quiet might descend on the landscape, a melancholic silence caused by an explosion in the amount of chemicals in use for farming and gardening. She passionately advocated for insects and birds, against the use of poisons directed towards the earth that provides our food, trying to disrupt the big players in the system with evidence-based arguments. Parts of America had already fallen terribly silent by 1962.

Here, the mantle of destruction has continued on a piecemeal basis, so that many farmland and garden birds have diminished dramatically in numbers of the last 50 years. The baseline has shifted to a new normal, we gradually fail to notice until songs are no longer sung.

We can act for birds, quite simply. Plant a tree in your garden or a group of trees if you have space, choose from the list of deciduous trees that are native to Ireland if you can – such as ash, rowan, hazel, holly. Encourage insects, leave seed heads in your garden, provide water. Farmers can plant corners of fields, where the big machines in use now cannot access at any rate or leave areas of gorse and scrub. We evolved on the planet alongside these creatures, and we must recognise that we are part of the same evensong. Welcome birds into your life, they will sing, and your heart will too.

Birdwatch Ireland, the charity in Ireland, which advocates for birds and their habitats has useful resources on their website.

The Gardening for Biodiversity booklet is available at https://www.chg.gov.ie/how-irish-families-can-cultivate-na…/

Or by emailing shclerkin@monaghancoco.ie for a hard copy.

Photograph of two blue tits by Richard Duff.

Day 49- Exploring heritage through the Schools Collection

Fifty thousand school children participated in collecting the local history and heritage of their localities in the years 1937-1939, as part of an innovative project established by the Irish Folklore Commission. A massive undertaking, supported by the primary school teachers across 5,000 schools, the children interviewed their parents and grandparents in an inter-generational effort on a range of subjects including legends, folklore, placenames, gaelic words, crafts and recipes.